It was a month ago when I became another statistic – my car vanished from my driveway in the dead of night. As a cybersecurity journalist for carparteu.com, I’ve written extensively about vehicle vulnerabilities, but this time, the story was personal. This isn’t just about my experience; it’s about the rising tide of car theft and the methods criminals are using, often involving exploiting the OBD2 port. While my Mercedes-Benz was the victim, understanding how these thefts happen is crucial for all car owners, especially in the face of evolving threats like “Hack Indrive Obd2” techniques.

For context, specifying my car make isn’t about vanity. It’s relevant because Mercedes, among other brands, are frequently targeted, and their technology plays a role in these thefts. And for the record, it was the nicest car I’d ever owned – hardly a luxury symbol, but a significant loss nonetheless.

Having covered cybersecurity for 18 years, including car hacking and even interviewing experts like Charlie Miller, I, like many, had a degree of detachment. I understood the risks intellectually, but fell into the trap of thinking “it won’t happen to me.” A classic mistake, and one that many car owners make until it’s too late.

I’m now among the hundreds of thousands who experience car theft annually in the UK. However, my profession allows me to tap into a network of experts, providing insights and explanations that can benefit others facing similar situations and seeking to understand terms like “hack indrive obd2” in the context of modern vehicle theft.

The Shocking Scale of Car Theft

The latest figures from the DVLA paint a grim picture: a car is stolen roughly every eight minutes in the UK. Analysis from the Office of National Statistics reveals a staggering 397,264 car thefts in England and Wales between October 2022 and September 2023. This figure, often understated in media reports, underscores the severity of the problem.

Land Rover tops the list of most stolen vehicles, with Mercedes and Ford following closely – rankings no manufacturer desires. Recovery rates are equally disheartening, with most data suggesting less than 20% of stolen vehicles are ever recovered.

This reality raises a critical question: how are so many cars stolen silently, without forced entry, often overnight? The answer, increasingly, lies in sophisticated methods that exploit vehicle technology, including techniques related to “hack indrive obd2” and similar vulnerabilities.

Was My Car Hacked? The Likely Method

My stolen vehicle was a Mercedes-Benz GLC 220 AMG Line Premium D, crucially equipped with keyless entry and start. The detective investigating my case informed me of six similar thefts within a mile radius over two nights, pointing towards organized crime groups operating in the Oxfordshire area, likely traveling from larger cities like London or Birmingham.

“Six cars of a similar calibre were stolen from within a one-mile radius over two evenings”

Discovering my driveway empty on a February morning was a stark awakening. Both car keys were in their usual places. My partner confirmed he hadn’t moved the car, and there was no sign of forced entry on our secluded driveway. The conclusion was almost immediate: my car was likely hacked. But what kind of “hack indrive obd2” or similar method was used?

“I’d say so, yes,” confirmed Graham Cluley, from the Smashing Security podcast. “In its broadest sense, hacking is gaining unauthorized access, and the thieves who stole your car did exactly that by exploiting a vulnerability in its entry system.”

David Rogers, CEO of Copper Horse, a connected car security specialist, concurred: “It’s almost certainly car hacking.” Most experts I consulted agreed, attributing it to some form of electronic exploitation.

Adam Pilton, a former police officer and cybersecurity consultant at CyberSmart, offered a slightly different perspective. “While ‘car hacking’ sounds sophisticated, the theft of multiple cars in a short period suggests a relay attack, a simpler yet highly effective method.” This raises the question: is a relay attack a form of hacking, especially when considering the intention to then potentially use OBD2 for further exploitation, akin to a “hack indrive obd2” scenario?

Ivan Reedman of IOActive provided a contrasting viewpoint: “If we define hacking as gaining unauthorized access to data in a system, then this might not be strictly a ‘hack.’ The criminals gained access to the car, but not necessarily data. So, is it theft, or a hack?” The nuance lies in whether exploiting a system’s vulnerability to gain physical access constitutes a ‘hack’ in the cybersecurity sense, especially when considering the subsequent potential for deeper system intrusion via OBD2.

Relay Attacks: The Common Denominator

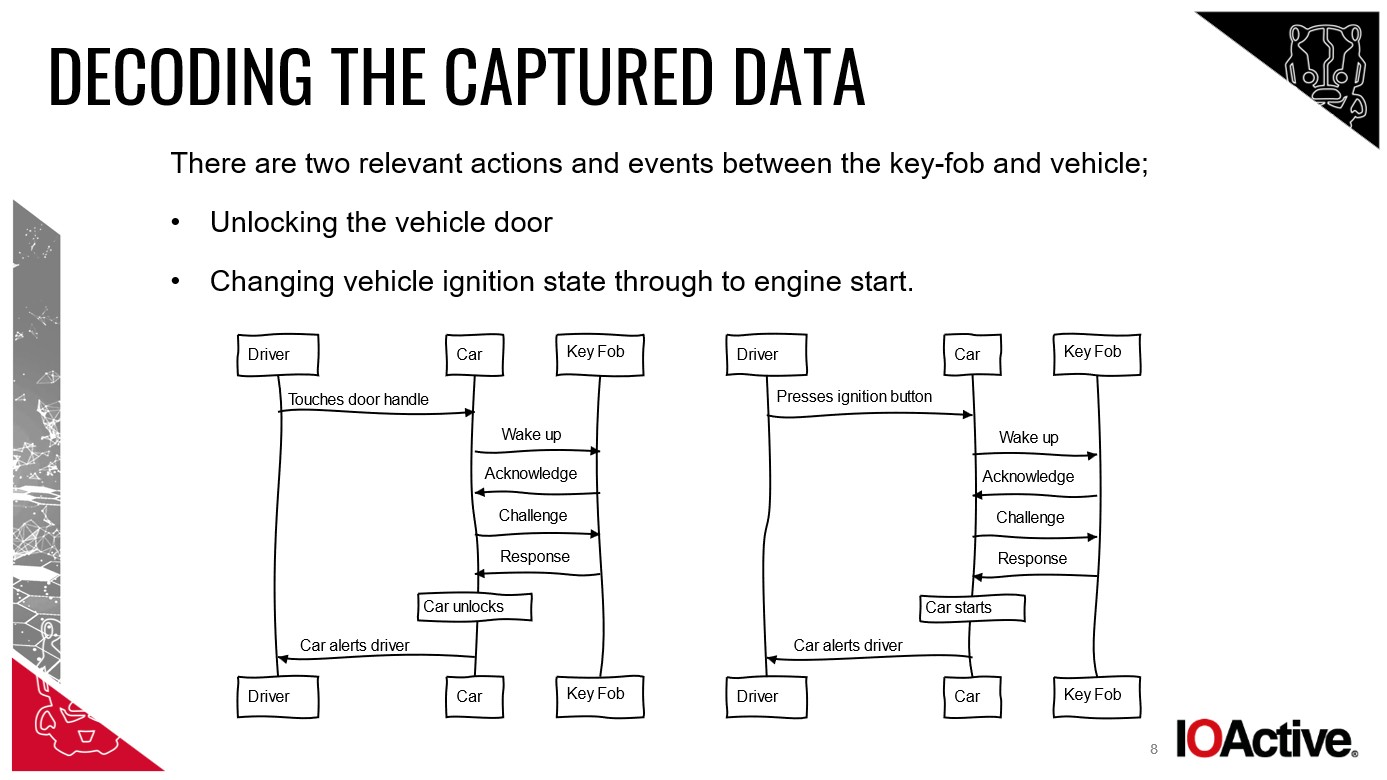

Despite differing definitions, all eight experts I interviewed agreed on the likely method: a relay attack. My Mercedes featured Passive Entry Passive Start (PEPS), meaning as long as the key was nearby, I could enter and start the car without pressing buttons.

“Relay attacks are one of the simplest attacks, requiring no [technical] knowledge or secrets” – Ivan Reedman

Chris Pritchard, an adversarial engineer at Lares, explained, “Thieves use a tool and antenna to relay the signal between your key and car. The car is tricked into thinking the key is close by, unlocking the doors.”

William Wright, CEO of Closed Door Security, added, “They use two devices. One near your house to capture the key fob signal, even through walls, and another near the car to relay that signal.”

These relay devices need to be within just 10-15 meters of the key and can operate in about 30 seconds.

Reedman elaborated, “When the device near the key relays the signal to the car, it creates a range extension, allowing thieves to enter and drive off. This attack effectively extends the operational range of the PEPS system.”

Understanding the signal relay process in keyless entry systems.

Reedman, who even demonstrated this attack for the BBC using basic components, emphasized the simplicity: “Relay attacks are one of the simplest attacks, requiring no technical expertise.”

But how do they continue driving after the car realizes the key isn’t present? “Once started, most cars will warn about the missing key but won’t shut off the engine. It will run until stopped, at which point thieves often use the OBD2 port to assign a new key and disable the original,” Reedman clarified. This step, involving the OBD2 port, is crucial for long-term theft and is where the concept of “hack indrive obd2” becomes more relevant, as OBD2 access allows for deeper vehicle control beyond just starting and driving immediately.

Cluley added, “The car won’t stop if it loses key signal – that would be dangerous if the key battery died. But it likely won’t restart.”

OBD2 Access: The Next Stage of the Theft

Relay attacks get thieves into the car and started. But to truly steal it long-term, they need to bypass security measures and ensure they can restart the vehicle. This is where the On-Board Diagnostics (OBD2) port becomes critical. “Access to the OBD2 port allows triggering the car to start using other devices,” Rogers explained. “By fooling the car into thinking there’s legitimate access, there’s no reason to prevent driving.” This OBD2 manipulation can be considered a deeper level of “hack indrive obd2” as it involves system manipulation beyond just signal relay.

Pritchard described the likely tool: “An OBD2 programming tool. It’s a port under the steering wheel, used by mechanics for diagnostics and resetting lights.” He shared his own experience: “When my Audi was stolen for an armed robbery, they broke in and programmed a new key via the OBD2 port. Something similar likely happened here.” This OBD2 access allows for key cloning or reprogramming, solidifying the theft and enabling long-term use, directly aligning with the idea of a “hack indrive obd2” to fully control the vehicle.

While key cloning itself is complex, accessing and manipulating the OBD2 port is a more straightforward method for thieves to gain persistent control. Experts dismissed the idea of complex key cloning attacks in my case, emphasizing the efficiency and prevalence of OBD2 exploitation after the initial relay attack.

Debunking the Flipper Zero Myth

Despite initial suggestions on social media about Flipper Zero attacks, experts largely dismissed this possibility in my case. While I initially mentioned the incident on Twitter (now X), early responses included theories about Flipper Zero being involved.

The Flipper Zero device, often mistakenly linked to sophisticated car thefts.

However, armed with the full details of the theft, experts deemed Flipper Zero involvement “highly improbable,” as Reedman put it, a sentiment echoed by others.

Pritchard directly addressed the Canadian government’s ban on Flipper Zero, “As much as Canada would like to blame Flipper, this isn’t a Flipper attack.” While Flipper Zero is a versatile tool capable of various wireless exploits, it’s not typically associated with the relay attacks and OBD2 manipulation seen in modern car thefts. Its capabilities are often overstated in relation to sophisticated auto theft, and in the context of “hack indrive obd2”, the focus is more on OBD2 programming tools rather than devices like Flipper Zero.

The Human Element: Who are the Thieves?

Having understood how my car was stolen, the question shifts to who is behind these thefts and how they acquire the skills and tools.

“The technique is well-known among car thieves, and information on how to do it is readily available online,” Cluley explained.

Rogers emphasized the accessibility of car theft equipment: “Car theft tools are astonishingly easy to obtain. Most car thieves lack technical expertise; they simply operate pre-built devices.” The real expertise lies higher up the criminal chain. “The individuals in the R&D and supply chain who create these criminal products are largely untouchable, often involved in broader criminal activities like creating skimming devices for ATMs.”

Pilton added, “The tools aren’t specifically designed for car theft. They’re often repurposed communication or signal extension tools, much like a crowbar. The individuals committing the theft might just be using pre-configured tools provided to them.”

Reedman reinforced the low-skill nature of relay attacks, diminishing the “hacking” label in its traditional sense. “It requires minimal skill. They likely watch online videos and purchase relay equipment. It’s quite trivial.” True hacking, he argues, demands a higher level of technical proficiency.

Shockingly, reports indicate children as young as 10 have been arrested for car theft, highlighting the ease of these methods. Direct Line Motor Insurance reported over 1,156 individuals under 18 charged with vehicle theft in three years, further demonstrating the accessibility and low barrier to entry for these crimes. “They probably learned to drive on Mario Kart and GTA V,” Cluley wryly commented.

Automakers’ Response and Responsibility

With car theft rising, particularly targeting keyless entry vehicles, manufacturers face increasing pressure to enhance security. Wright argues, “The automotive industry lags behind most in technological attack protection.”

I contacted Mercedes-Benz, posing questions about keyless vehicle theft and manufacturer accountability. A spokesperson, preferring anonymity, stated, “The security of our organization, products, and services is a top priority in our R&D activities.”

Vehicle security updates are often implemented in newer models, leaving older cars vulnerable.

The spokesperson noted that from mid-2019, the GLC “facelift version” incorporated a motion sensor in the key, deactivating KEYLESS GO when the key is stationary, thus preventing relay attacks. My 2018 model predated this update.

“Our keys also offer an option to temporarily disable KEYLESS GO, preventing compromise even by range extenders.” Additionally, Mercedes highlighted the Mercedes me service, allowing users to deactivate keys via the app if lost or stolen, and the GUARD 360° ‘stolen vehicle help’ function for reporting theft and vehicle location assistance. However, they didn’t address why the KEYLESS GO disable option isn’t proactively presented to customers at purchase.

Shifting Blame and Neglecting Security

“Car manufacturers prioritize ease-of-use over security,” Pritchard contended. The surge in Range Rover thefts led JLR to introduce its own insurance as owners faced unaffordable premiums, highlighting the severity of the issue.

Rogers believes manufacturers lack understanding of the criminal ecosystem and urgency in addressing new theft techniques. “Solutions exist for quick deployment, but there’s a reluctance to admit the problem and act.”

“Car manufacturers continue to push ease-of-use functionality over security” – Chris Pritchard

Victim-blaming is common, Rogers noted. “Owners are told to keep keys away from ground floors or block cars with non-keyless vehicles. This is wrong – the negligence lies with manufacturers. They know about vulnerabilities but often do little. However, manufacturers are also victims; international law enforcement needs to better tackle organized crime.”

Some manufacturers are implementing updates, like accelerometer-equipped key fobs that enter sleep mode when stationary. Others use positioning technology to verify key proximity. However, proactively informing car buyers about keyless entry risks at the point of sale seems a basic step. Manufacturers often emphasize convenience, but balanced information about security vs. convenience is crucial.

Cluley added, “Manufacturers have known about these risks for years, but solutions are slow to roll out, likely due to cost and time.”

Pilton advocates for shared responsibility, emphasizing collaboration between manufacturers, software developers, and regulatory bodies. “Prevention should include minimum security standards and empowering informed consumer decisions.”

The Criminal Justice Bill: A Step Forward?

The UK’s Criminal Justice Bill, introduced in November 2023, aims to criminalize the possession of electronic devices used for vehicle theft. The Bill targets “signal jammers used in vehicle theft and strengthens Serious Crime Prevention Orders.”

Rogers, however, raises concerns from the security research community. “It could chill security research due to potential arrest risks while using such technology for legitimate research to prevent theft and find security flaws.” The Bill is still under review, offering potential for refinement.

The Appeal of “Dumb Cars”

Criminals often target the easiest opportunities. Relay attack car theft is attractive due to its simplicity, lack of forced entry, and minimal risk of detection. “It’s a low-risk crime with no vehicle damage, maintaining resale value for criminals,” Pritchard explained.

“While traditional key-based systems have weaknesses, keyless entry increases vulnerability to specific attacks,” Pilton noted.

No surprise then that Cluley is “very glad to have a dumb car.”

Following my car theft, I received countless similar stories on social media, highlighting the widespread nature of the problem, low recovery rates, and rare prosecutions.

The Challenge of Prosecution

Wright laments the “very poor” success rates in prosecuting car thieves due to the ‘smash and grab’ nature of relay attacks. “They’re gone quickly, tracking disabled, plates changed before police are called. The car is likely overseas within a day.”

Rogers mentioned successful “stings” targeting international car smuggling rings, but these address symptoms, not the root cause. “Tackling international criminal tool makers would significantly impact lower-level criminals.” “Chop shops,” where stolen vehicles are dismantled for parts, are also a persistent problem.

Modern car theft often leaves no trace, unlike older methods.

Pilton described his law enforcement experience pursuing car thieves, often finding crashed and abandoned stolen vehicles. “Investigating overnight disappearances can be exceptionally difficult, even impossible.”

“Combating this crime is challenging for law enforcement. Cars are sometimes located, often burnt out or already abroad. Prosecution is difficult without direct evidence linking suspects to individual thefts. However, organized crime groups often leave ‘breadcrumbs,’ allowing law enforcement to build a broader picture and take action.”

A month after my car theft, there’s no trace of it or the other stolen vehicles. The detective suspects my car might have been used for ATM ram-raiding due to its size, or it could be abroad or in a chop shop. The investigation is ongoing, including forensic analysis of recovered plates and tracking data from embedded SIMs. However, recovery seems unlikely, and even if found, it belongs to the insurance company. Hope remains for answers and perhaps prosecution, but realism prevails.

Securing Your Keyless Car: Practical Steps

On the night of the theft, my key was in a drawer at the back of the house, a naive attempt at security. My cybersecurity background should have made me more aware of relay attacks. Regretfully, my professional cynicism didn’t extend to my own car security.

Now, I’m acutely aware. I asked experts for keyless car protection advice. The unanimous answer: Faraday.

“Use a Faraday box or wallet to block key signals and always store keys in one at home,” Cluley advised. Include spare keys too.

“The material used in Faraday pouches deteriorates after a matter of weeks, leading to signal leakage” – Dan Bulman

Reedman recommends testing Faraday effectiveness: “Try unlocking your car with keys in the box. If it works, a one-way relay attack might succeed. If not, a one-way relay will likely fail, but two-way attacks are possible.” He suggests a fully enclosed metal box for maximum security.

The old advice of keeping keys far from the front door still holds.

Rogers suggests disabling keyless ignition if possible, using a mechanical steering lock, and considering an OBD2 port lock to deter OBD2-based attacks and manipulation related to “hack indrive obd2”. “OBD2 port locks are available online, making diagnostic port access inconvenient for thieves.”

Pilton emphasizes social media awareness to educate others about the risks and encourage preventative measures.

Just before publishing this article, Dan Bulman of KEYSHIELD contacted me about their device, claiming “100% protection against key cloning and relay theft.” The KEYSHIELD sleeve disables the key battery when stationary using motion sensor technology, preventing signal emission after 20 seconds of inactivity. Testing on my new car, however, resulted in the KEYSHIELD working too well, preventing even legitimate access and triggering the alarm. Bulman is investigating potential incompatibility issues.

For my new car, I’m adopting a “belt and braces” approach: Faraday box and a steering wheel lock. Cynicism fully restored, and this time, proactively applied to my own car security.

This is the story of my car theft, explained in detail. Until manufacturers prioritize security and educate owners about vulnerabilities and options, articles like this aim to empower car owners with knowledge and encourage proactive security measures against methods like “hack indrive obd2” and relay attacks.